It may surprise many that, in global terms, girls make up just 52% of out of primary school age children. At the secondary level there are actually fewer girls out of school than boys. When averaging out the gender parity index across all countries, you will find that gender parity has actually been achieved globally in both primary and secondary education.

Given the loud cries for girls to be prioritized in education policies these facts don’t add up. Why?

For a start, many countries with large populations – in particular, India, Brazil and China – have achieved gender parity in primary education and constitute a large slice of the global pie. Global figures cover up the entrenched disparities faced by girls in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and in parts of South and West Asia and the Arab States, where populations are relatively smaller. At the secondary level, many countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have disparities at the expense of boys, not girls. This, together with more conventional disadvantages faced by girls in other regions, creates a seemingly balanced global portrait.

It is a rare occasion where a global figure puts a positive gloss on a story, as is the case with gender. But the fact remains that global gender figures obscure large gender gaps in many different countries. For example, they don’t show that there are five times more countries with extreme gender disparities at the expense of girls than of boys in primary school. Nor do they show that almost half of out-of-school girls of primary school age will never set foot in a classroom, equivalent to 15 million girls, compared with just over a third of the boys. The proportions in sub-Saharan Africa are even worse.

It is precisely because of how extreme gender gaps are at the expense of girls, and how entrenched their disadvantage is that any projections for primary or secondary completion rates are so revealing. The GMR 2013/4 showed, for instance, that the poorest girls in sub-Saharan Africa would achieve lower secondary completion more than 20 years later than the poorest boys.

There is, therefore, solid reasoning behind advocates calling for girls to be prioritized. It requires an understanding of the impact that different contexts can have on gender gaps, and explains why it is that the poorest girls are the furthest behind of all. It is wrapped up in the knowledge that, in addition, girls’ education has even stronger positive effects on development outcomes.

To help visualize the complexities of this story, the EFA GMR has developed an online interactive tool to show the extent to which specific contexts influence the size of the #gender gap in different countries and regions.

It shows, for instance, that in sub-Saharan Africa, the poorest girls are almost nine times more likely never to have set foot in a classroom than the richest boys.

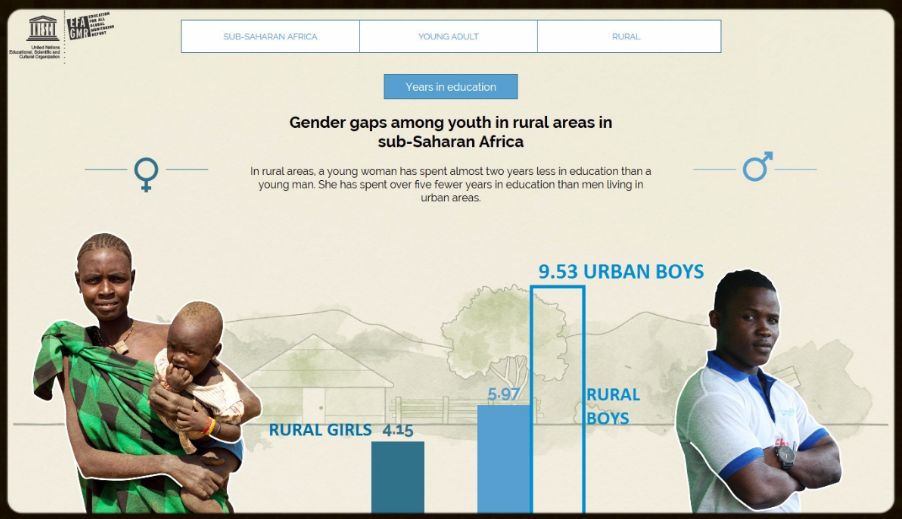

Rural young women in sub-Saharan Africa have on average spent at least five years fewer in education than men living in urban areas.

In the Arab States, the poorest females are almost two and a half times less likely to complete lower secondary education than the richest men.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, however, the graphic shows clearly that boys are at a disadvantage: 55% of boys compared to 63% of girls in rural areas complete lower secondary education.

The figures used in this tool are taken from the EFA GMR’s Worldwide Inequalities Database on Education (WIDE). It is a crucial instrument for understanding the real impact of disadvantages such as gender, wealth, language and location on unequal education outcomes in countries around the world. It shows that what may seem one story on the surface is another story in reality. It illustrates how an equity perspective can help us to better analyse progress towards the new post-2015 education agenda.